Learning from the S&P500

In his famous commencement speech at Kenyon College, David Foster Wallace shared a simple yet profound anecdote: Two young fish are swimming along when an older fish swims by and says, "Morning, boys. How’s the water?" The two young fish continue on, and eventually, one looks at the other and asks, "What the hell is water?" This story illustrates how the most pervasive and essential aspects of our environment can go unnoticed.

For investors, the S&P 500 serves as a similar backdrop. The S&P 500 is the world’s most widely followed and most liquid index; the 500 companies in the index account for approximately 80% of the entire U.S. equity market capitalization. Just as fish might be unaware of the water around them, many investors don't fully understand the composition and dynamics of the S&P 500, the very benchmark they strive to outperform.

Over the long term, research consistently shows that the large majority of active managers underperform this index. The latest ‘S&P Indices Versus Active’ (SPIVA) report highlights that 88% of active managers have failed to beat the S&P 500 over the last 15 years. If the S&P 500 were a fund manager, it would consistently rank in the top quintile of active managers. There’s something to learn in that consistency and reliability.

In this blog post, we will look under the hood of the S&P 500 to discern lessons we can take from the index and how it achieves such remarkable performance.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices

Betting on America

Over the past century, America’s stock market has been an extraordinary engine of wealth creation. This success can be attributed to America's abundance of natural resources, an empowered middle class, a global language, a welcoming society, and an indomitable entrepreneurial spirit. These factors have given rise to countless remarkable businesses. The very traits that define the world’s leading companies—decentralized decision-making, autonomy, acceptance of failure, uncapped potential, and relentless innovation—are also emblematic of America itself. These characteristics have provided the U.S. with a significant advantage over many other countries and remain as influential today as ever.

The insightful '2023 Credit Suisse Global Investment Year Book' highlights the long-term outperformance of the U.S. market, noting that it "reflects the superior performance of the US economy, the large volume of IPOs, and the substantial returns from US stocks. No other market can rival this long-term accomplishment." Over the last c120 years, c50 years, and c20 years, U.S. equities have delivered annualized real returns of 6.4%, 5.9%, and 7.1% respectively, outperforming world markets ex-US by 1.5% to 2.1% per annum.

While the S&P500 has experienced significant drawdowns, every single US stock market crisis prior to today had one common characteristic: they bottomed. Each went on to record highs.

Source: 2023 Credit Suisse Global Investment Year Book

Return on Capital

While stock prices and share markets can be highly volatile, the underlying returns on capital for US businesses have remained relatively stable. Warren Buffett observes, "Anyone who examines the aggregate returns that have been earned by companies during the postwar years will discover something extraordinary: the returns on equity have in fact not varied much at all." This return has been attractive, as Chuck Akre noted, "the real return on equity of American businesses averages in the low teens." Over the long term, both a company and the market will reflect the underlying earnings driven by these returns on capital. Sir John Templeton has noted, "In the long run, stock market indexes fluctuate around the long-term upward trend in earnings per share."

Retained Capital

Not only has the S&P500 outperformed most geographic equity markets over the long term, it has also outperformed every other asset class. There’s a good reason for this. Fundsmith’s Terry Smith explains, “Equities can compound in value in a way that investments in other asset classes, such as bonds and real estate, cannot. The reason for this is quite simple: companies retain a portion of the profits they generate to re-invest in the business.”

Source: Credit Suisse Global Investments Yearbook 2023

Return on Investments

One reason the S&P 500 has delivered strong returns is the disciplined approach companies take towards capital investment. Research by John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey supports this, showing that CFOs do not significantly adjust their required returns even when market interest rates decline. This capital discipline, combined with the robust economic and entrepreneurial environment in the US, allows many S&P 500 companies to sustain high returns on capital over time.

Loss Aversion

The S&P 500 is unemotional. Many investors, influenced by loss aversion, get spooked by geopolitical events, macro-economic concerns, or market declines, prompting them to sell at the lows or exit positions prematurely. Seeking the security of cash, they wait for calmer times to re-enter the market. It is no wonder that, according to renowned research firm Dalbar Inc., the average investor has underperformed the index by more than 2% annually over the last 30 years. As Chuck Akre reminds us, "Every basis point of return—let alone 100 basis points—has a staggering difference in outcomes in the long run." In contrast, the S&P 500 never gets shaken out of the market and never ‘sells the lows,’ avoiding the cardinal sin of investing.

Anchoring Bias

Companies are removed from the S&P 500 when they fail to meet minimum market capitalization thresholds or face financial difficulties. Once a company is removed from the S&P 500, it can be considered as a replacement candidate one year after its removal date. Should the company fulfil the index inclusion requirements, it can re-enter the index. Even the world’s greatest investors struggle to buy back stocks they’ve sold at lower prices. As Buffett has noted, "It’s a little hard when you looked at something at X and it sells at 10X to buy it. It shouldn’t be, but I can just tell you psychologically it’s harder... It’s cost people a lot of money."

Cutting Losses

Most turnarounds don’t turn. The index is unemotional when it comes to cutting losing positions - it’s systematic. There’s no commitment or confirmation bias or endowment effects. When a stock is out, it’s out; no changing the thesis to justify keeping the position. This differs from the behavior of many investors.

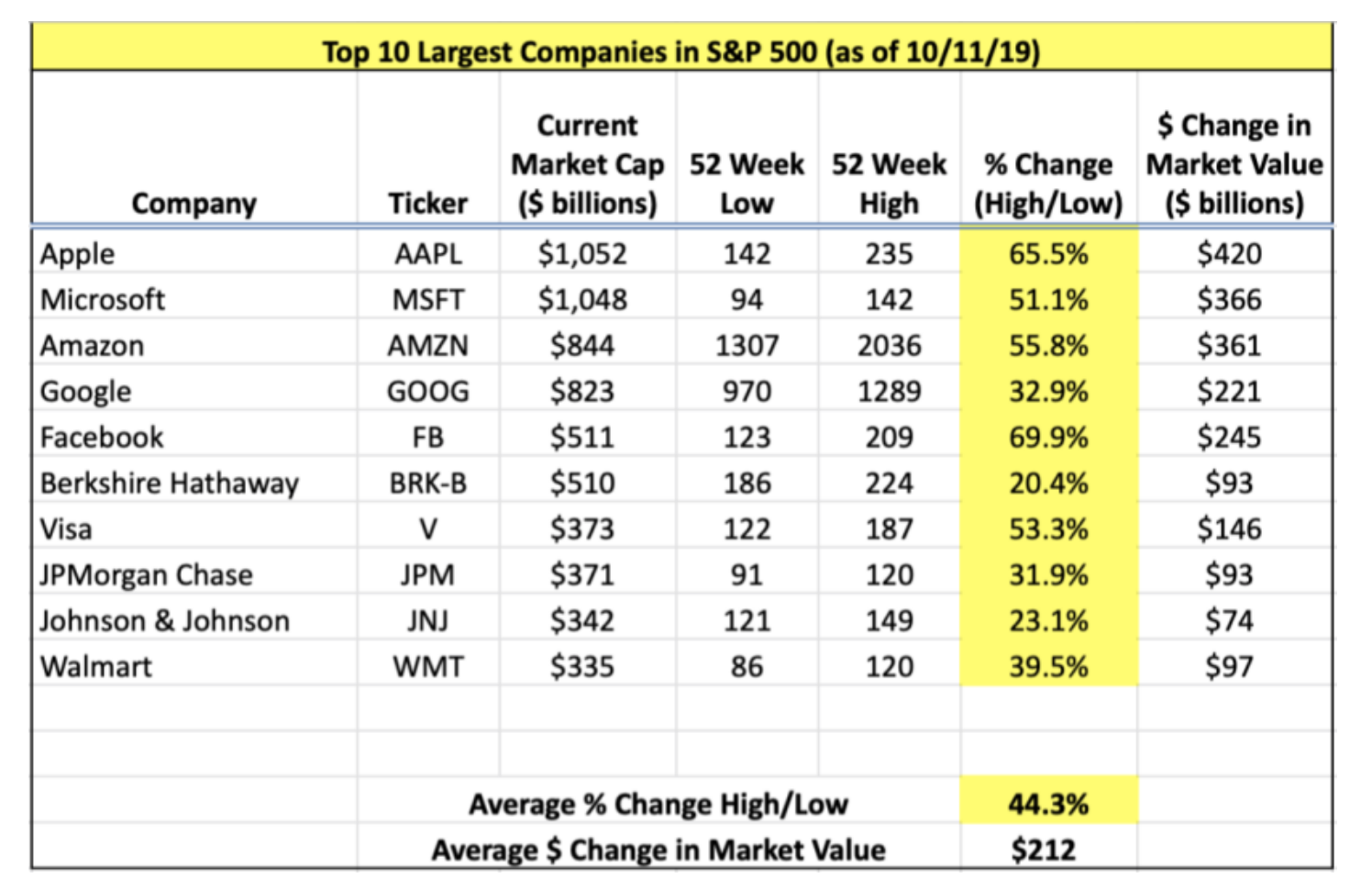

Portfolio Weightings

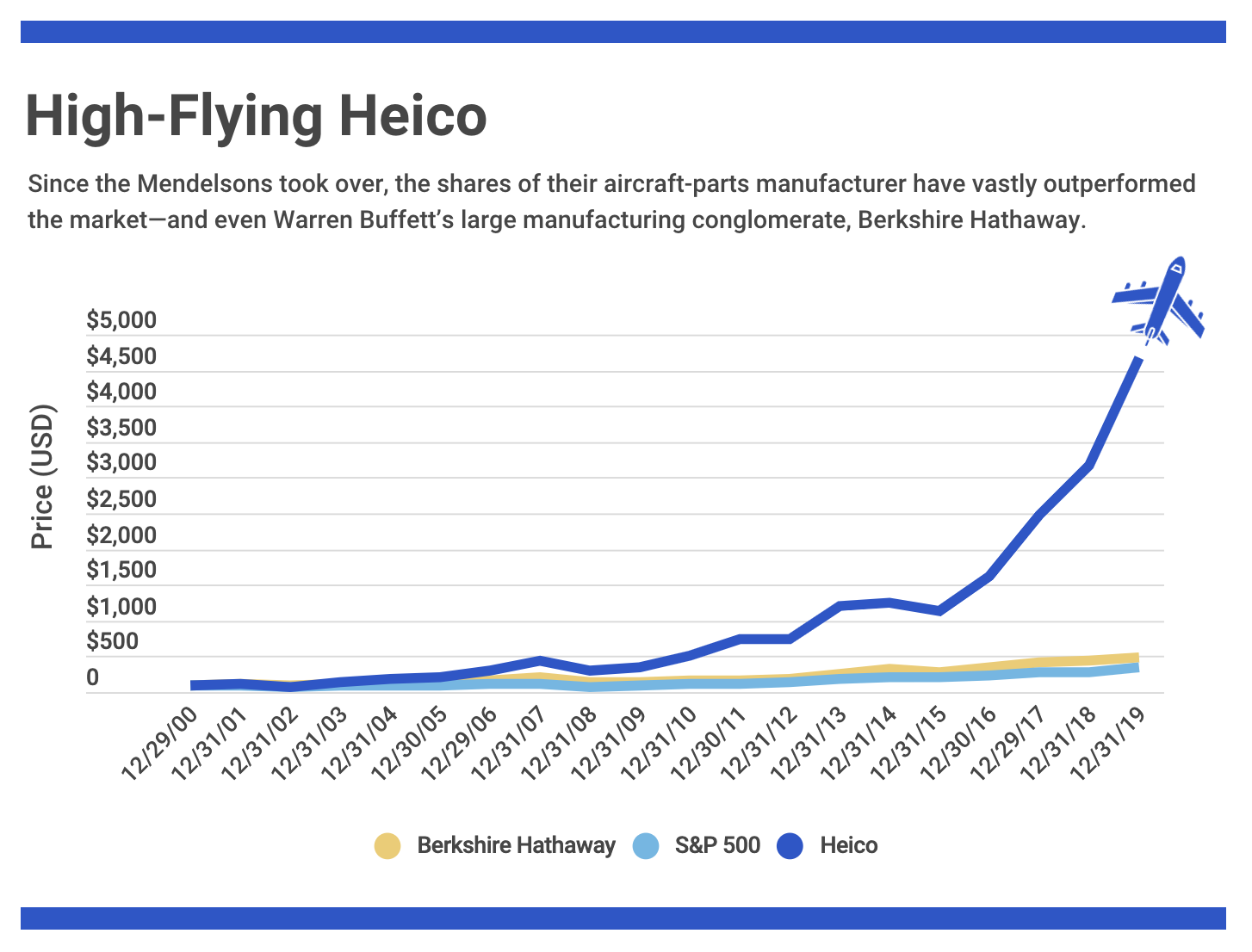

The index won’t sell stocks based on portfolio or sector weights. Most investors sell or re-weight their winners when they become too large a position in their portfolios. It’s challenging for a fund manager to attract capital when a single stock comprises, say, over 20% of a portfolio. A good example is Amazon.com since its IPO. A portfolio with a 4% position in Amazon in 1997, with the balance representing the S&P 500, would today consist of 89% Amazon and 11% in the S&P 500—an allocation no active fund manager would be willing to hold. The only investors who don’t sell tend to be the founders, some employees and of course the S&P500 index.

Complex Adaptive Systems

The stock market is a complex adaptive system; the whole is more than the sum of the parts, subject to non-linear outcomes and impossible to forecast. Exponential stock returns are a feature. Hendrik Bessembinder, a professor at Arizona State University, looked at 90 years of US stock market data. What that showed is that of the 26,000 companies you could have invested in over that period, all of the return came from just four percent of the companies. Oftentimes, these can be controversial and optically expensive companies, strongly polarising the views of market participants. If you don’t own these rare outliers - the multi-baggers - it can be hard to outperform the index.

Errors of Omission

Many fund managers reflect on missed opportunities as their most significant regrets. Once a company meets the S&P's eligibility criteria, it is typically included, regardless of fundamental analysis, valuation considerations, or price targets. Although a company's initial position in the index may be modest, the power law of returns and market capitalization-based weighting means it could become a significant contributor over time. While the initial investment size might be smaller compared to a typical active fund position size, it still secures a place in the S&P500 portfolio, illustrating why fund managers often struggle to beat the index.

Over-Confidence

Famed investor, Chris Browne, stresses the importance of ‘calibrated confidence’ in investing, acknowledging our limitations. Research reveals that overconfident investors tend to trade more, resulting in lower returns. In a study of 100,000 stock trades, sold stocks outperformed bought ones by 3.4% after a year. High portfolio turnover reflects misplaced confidence, while lower activity levels often lead to better returns. Notably, index turnover is minimal.

Sitting Still

An annual fund manager’s report stating, ‘we did nothing all year,’ is likely to attract significant scrutiny. Asset owners, consultants, and allocators expect their fund managers to be active. Nevertheless, the decision to do nothing is still a decision. Charlie Munger sums it up nicely: “For an ordinary person, can you imagine just sitting there for five years doing nothing? It’s so contrary to human nature. You don’t feel active. You don’t feel useful, so you do something stupid.” Frenetic investment activity often undermines long-term performance, providing another edge to the S&P500.

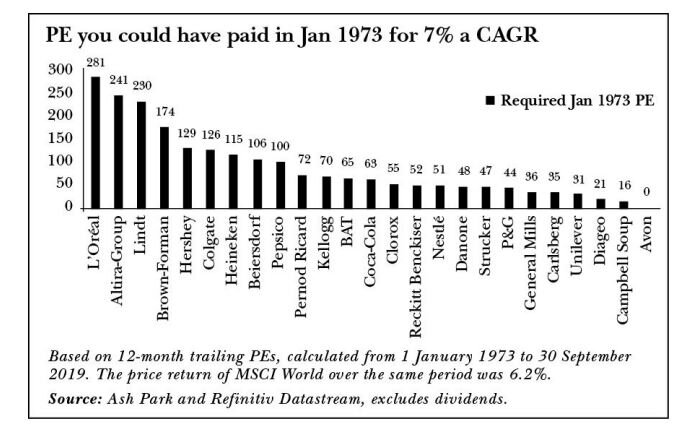

Valuation Concerns

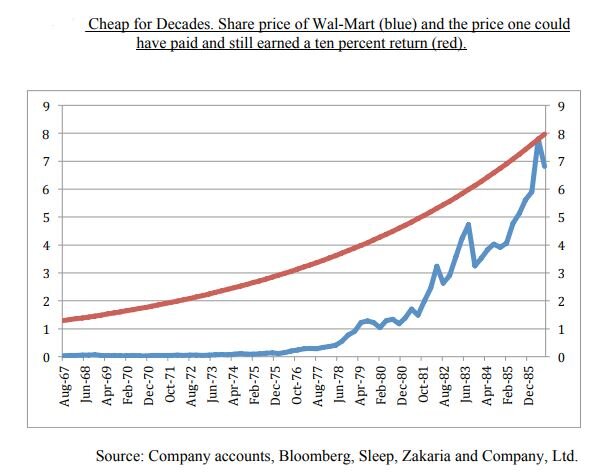

High quality companies can become and remain optically expensive yet continue to deliver market beating long term returns. Many of the world’s greatest investors will tell you their most costly mistake has been what they’ve sold, not what they’ve bought. It’s psychologically hard to buy back a stock you sold at a lower price. Selling a stock that looked expensive, which goes on to compound 10-fold or 20-fold is not a problem the index will have.

Large Companies

The S&P500 comprises large companies requiring a minimum market capitalization over US$18 billion. These companies must be listed for at least one year and have a track record of profitability to meet certain inclusion criteria. In contrast, as Charlie Munger has noted, “It’s the nature of things that most small businesses will never be big businesses.”

Costs

The S&P500 holds a distinct advantage for investors when it comes to costs. Unlike actively managed funds, which frequently engage in stock turnover, index funds minimize frictional expenses like brokerage fees and bid-ask spreads. Active managers' frequent buying and selling also tend to generate higher capital gains taxes for investors. Furthermore, these actively managed funds typically charge fees ranging from 20 to 200 basis points, sometimes even including performance fees. In contrast, S&P500 index funds offer significantly lower fees, allowing investors to retain more of their returns over the long term.

Summary

In the realm of investing, human psychology often proves to be a significant hurdle. It's often noted that the best-performing accounts of private clients are those belonging to individuals who are either deceased or have forgotten about their existence. This phenomenon underscores the emotional biases that can impede investors—biases that the S&P 500 largely sidesteps.

While individual investors grapple with loss aversion, anchoring bias, overconfidence, and the challenge of simply sitting still, the S&P 500 remains steadfast. Its systematic approach to managing portfolios is immune to the cognitive biases that often plague human decision-making. Many of the world's most revered investors, such as Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Charles Ellis, Howard Marks, Terry Smith, Peter Keefe, Lou Simpson and Nick Train, advocate for the S&P 500 as an ideal vehicle for capital deployment for the average investor.

For many, learning from the S&P 500 is akin to realizing the water you swim in. It's everywhere, yet often overlooked. Just as fish might finally grasp the concept of water, investors can glean valuable insights from the S&P 500, navigating the financial seas with a clearer understanding of their surroundings—and hopefully avoiding the occasional undertow of irrational decision-making.

Sources:

‘Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2023,’ Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh, Mike Staunton, Credit Suisse Research Institute.

‘SPIVA [S&P Indices Versus Active] Data,’ S&P Dow Jones Indices.

‘Dalbar QAIB 2024: Investors are Still Their Own Worst Enemies,’ Index Fund Advisors, 2024.

‘Do stocks outperform Treasury Bills?’ Hendrik Bessembinder, Journal of Financial Economics, 2018.

‘Corporate Finance and Reality,’ John R Graham, NBER, 2022.

Further Reading:

‘Betting Against America?’ Investment Masters Class, 2018

Follow us on Twitter : @mastersinvest

* Visit the Blog Archive *

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER

![S&P500 [grey] vs General Electric [blue] Normalised - 2000 - 2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1626240958557-MQY5UOVVQ98IF9CHHKM1/Screen+Shot+2021-07-14+at+3.33.36+pm.png)

![Dow Jones Industrial Average - 1987 Crash [Source; Bloomberg].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1616478903417-5MBL252INY28HCUPDPYG/dow.PNG)